Most H&D readers will be familiar with the National Front’s long tradition of marches to the Cenotaph in London’s Whitehall on Remembrance Sunday each year. Opponents of the NF have long objected that these marches “politicise” what should be a non-political tribute to loyal subjects of the Crown from across Britain and its Empire, who gave their lives in its defence.

Yet these marches began not as a politicisation, but as an effort to depoliticise the event after Harold Wilson’s Labour government excluded Rhodesians from the main Cenotaph ceremony. In fact the origins of the march are in 1966, the year before the NF was founded. Remembrance Sunday that year fell on the first anniversary of UDI – the Unilateral Declaration of Independence by Rhodesia’s pro-White Prime Minister Ian Smith.

Wilson and his leftwing government in London insisted that this meant there was no legitimate Rhodesian government, and the respective diplomatic missions in London and Salisbury were reduced to a residual staff. The Rhodesians were told that they would not be welcome alongside other Commonwealth representatives on Remembrance Day 1966.

Consequently a pro-Smith group – the Anglo-Rhodesian Society – organised its own event at the Cenotaph, attended by numerous Tories such as Monday Club officials Ronald Bell MP and the Marquess of Salisbury, as well as senior military veterans including Gen. Sir Nevil Brownjohn (Deputy Chief of Staff at Eisenhower’s Headquarters during the 1944 Normandy landings) and Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Longmore (Vice-Chairman of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission).

A Church of England priest – Rev. Stephen Pulford, Rector of the Herefordshire parish of Linton and Upton Bishop – was invited to conduct the service, but the organisers were embarrassed by his connections to the Racial Preservation Society, an anti-immigration pressure group that included the printer Alan Hancock (father of Tony Hancock, who took over the family printing business and will be remembered by many H&D readers).

So Rev. Pulford ended up merely being among the crowd. (It’s a sign of those very different times that the Sunday Telegraph headline reporting this change did not refer to “racists” or “fascists” but simply read: “Pro-white Rector ‘Dropped’”.) The Anglo-Rhodesian Society’s service was instead conducted by Commissioner William Cooper, head of the Salvation Army. The Band of the Scots Guards had originally accepted a booking to play at the service, but after consultations with the Ministry of Defence cancelled this booking and were replaced by a Salvation Army band.

Around 6,000 supporters of the Anglo-Rhodesian Society assembled in Whitehall for the ceremony, with a further 2,000 taking part in the march past the Cenotaph. Afterwards about 1,000 surged into Downing Street (then unprotected by gates), and had to be held back by police as they taunted Prime Minister Wilson who was inside Number 10.

It was suspected that this demonstration had been incited by the RPS and another anti-immigration group, the League of Empire Loyalists, working with Rhodesian intelligence officers, as well as by members of small “far right” groups including John Bean’s British National Party and Colin Jordan’s National Socialist Movement.

The Racial Preservation Society (including Rev. Pulford), LEL and BNP merged into the National Front at its formation in February 1967.

Younger readers more accustomed to left-wing “trendy vicars” might be surprised to learn that several churchmen were involved in the NF and allied groups during the 1960s and 1970s, including the Rev. G.H. Nicholson, Rector of Burghfield, near Reading; the Rev. Terry Spong, who had been a prison chaplain in Rhodesia before returning to England and taking a similar position at Brixton Prison; and Fr. Peter Blagdon-Gamlen, Rector of Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey, a staunch Anglo-Catholic who wrote in 1963 that “no West Indian has ever been to my church. I am English and proud of it. I have many relations in South Africa, two of whom were murdered by the niggers.”

During the early months of the NF’s existence, the Rhodesian intelligence service began to prepare plans for an even bigger propaganda coup at the 1967 Remembrance Day. Both Smith’s government and the allied South African intelligence service BOSS had friendly connections with A.K. Chesterton, chairman of the National Front, but recently released official documents show that Wilson’s government were even more worried by rather more mainstream Rhodesian sympathisers, including one of Britain’s greatest war heroes.

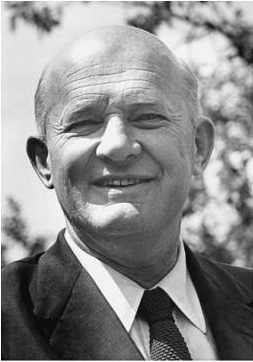

Group Captain Douglas Bader had joined the RAF in 1928 and as a twenty-one year old daredevil attempting acrobatic tricks had crashed his plane in 1931, losing both his legs and narrowly escaping death. Now legless, he retrained and was again able to fly, but was forcibly retired on medical grounds. In 1939 however, with the RAF now desperate for pilots, Bader was accepted again and became a remarkably successful fighter pilot despite his disability, until his capture in August 1941.

He was eventually sent to Colditz, the special camp for prisoners who persisted in trying to escape, and remained there until the Americans liberated the camp in April 1945.

Despite his almost four years as a German prisoner, Bader remained very friendly with his former opponents during the postwar years, regularly attending Luftwaffe reunions, and was on especially good terms with fellow fighter ace Adolf Galland.

By this time he was employed by the Shell Oil Company and by the time of the Rhodesia crisis he was managing director of Shell’s aircraft subsidiary. Meanwhile Bader’s celebrity grew when in 1956 he was portrayed by Kenneth More in a film of his life and exploits, Reach for the Sky.

When Smith declared UDI in November 1965 Bader was in South Africa, and during a speech to South African Air Force veterans he expressed his support for the Rhodesians: “I came through Rhodesia and if Mr Smith, who was one of us, had declared UDI before I left I should have had serious thoughts about changing my papers to Rhodesian nationality.”

During the spring of 1967, Bader was drawn into Rhodesian plans for a propaganda coup in Whitehall. They hoped that Britain’s most famous war hero would agree to be among their wreath-laying party.

Unknown to the Rhodesians, Wilson had a spy in their camp – the supposedly ‘right wing’ Conservative MP Henry Kerby, who had cultivated Chesterton and was invited on what the Rhodesians thought was a secret visit to their capital Salisbury in mid-May 1967 to help plan their propaganda campaign.

On his return Kerby promptly leaked the entire plan to the sinister retired colonel George Wigg, Labour MP for Dudley, who acted as Wilson’s adviser on security and intelligence matters.

I shall explain the full history of Henry Kerby and his strange career with both MI6 and MI5 (including his infiltration of Sir Oswald Mosley’s postwar movement, and his foiling of a KGB plot to manipulate supposedly anti-communist ‘Russian nationalists’) on another occasion: the British authorities are still attempting to keep parts of this fascinating but complex story secret, but they will fail to do so.

For the purpose of this article the important aspect is that Kerby was able to report to Prime Minister Wilson everything that was being plotted by his Rhodesian opponent Ian Smith (and by more ‘right-wing’ figures such as the Duke of Montrose, a minister in Smith’s government).

One of Kerby’s contacts and drinking pals in Salisbury was Wing Commander John Plagis, a decorated Spitfire pilot who was a good friend of both Ian Smith (himself a distinguished RAF veteran who had been severely wounded during the war) and Douglas Bader.

In June 1967 Kerby sent Wigg a copy of a letter from Plagis and explained that the latter “intends to fly over here on his (illegal) Rhodesian passport to lay a Rhodesian wreath on the Cenotaph. He will wear his gongs [Plagis had been awarded a DSO and two DFCs] and hopes to be accompanied by Group Captain Sir Max Aitken [son of the famous press baron Lord Beaverbrook, who had succeeded his father as proprietor of the Daily and Sunday Express and London Evening Standard]; Group Captain Douglas Bader; and Wing Commander Laddie Lucas [Bader’s friend and brother-in-law, who had a column in the Sunday Express].”

Wigg sent the file to Downing Street and both MI5 and MI6 were consulted. This entire paragraph referring to Bader, Lucas and Aitken was removed from the published version of this document when it was eventually released to the National Archives as part of a Ministry of Defence file. However, I was able to defeat the censors by finding one surviving copy of the letter in Wigg’s private archive.

There are persistent rumours that Bader considered joining the National Front, but like many other convinced ‘racists’ was put off by the anti-Jewish views of leading NF officials. Several RAF veterans (including Bader and Lucas) had developed business connections with prominent Zionists, in several cases actively assisting the Zionist theft of aircraft soon after the war.

Though Bader’s pro-Smith and pro-South African views were at one time well known, British officialdom – then and now – does not want Britons to know that some of their legendary war heroes (including the greatest hero of them all, Douglas Bader) were quite so heavily committed to the Rhodesian cause. Nor do they wish any publicity to be given to the extraordinary methods that were used to defeat the Rhodesian lobby.

Police and MI5 feared either further disorder or a propaganda coup involving the likes of Bader: though sections of the relevant files have been withheld, it seems certain that pressure was exerted on Bader and his friends to back down, probably via certain shady Jewish businessmen who were friendly with both Wilson and these RAF veterans. Such tycoons might not have been too keen on black Africans, and might have been doing good business themselves in Rhodesia and South Africa, but they didn’t want a publicity coup for “racists” in Britain, especially not when those “racists” had just begun to get their act together by forming the National Front.

One Rhodesian agent in London was Geoff Dominy, who worked with Alan Hancock and his comrades in the Racial Preservation Society and was one of five defendants including Hancock in the famous Lewes trial of 1967 under the new race law. All the defendants were acquitted, but Dominy died in mysterious circumstances: it has twice been alleged by Searchlight that he was murdered by British intelligence.

In the event the Rhodesians’ 1967 ceremony was led by Vice Admiral Sir Peveril William-Powlett, who had been Governor of Southern Rhodesia during the 1950s. A few hundred demonstrators rushed into Downing Street but were easily contained by police.

In 1968 there was further trouble when the Ministry of Defence prevented the band of the Middlesex Yeomanry Old Comrades Association from leading the Rhodesian parade to the Cenotaph: two buglers were recruited as last minute replacements. Tory MPs from the Monday Club – including John Biggs-Davison and Patrick Wall – turned out to support the Rhodesians, as did the Marquess of Salisbury and his son Lord Cranborne (a veteran of the Normandy campaign who later supported Roger Scruton’s Salisbury Review).

By 1969 the Anglo-Rhodesian Society’s parade had become almost an accepted part of Remembrance Sunday, taking place after the main event. The entire situation had become less heated, because it was now obvious that Wilson was not going to take military action against the Smith government. Some Rhodesians no doubt hoped that after Wilson lost the 1970 general election, the new Tory government of Edward Heath might relent and allow them to take part in the main ceremony.

But any such hopes proved fruitless. In one of his first acts as Conservative Party leader in 1966, Heath had sacked the pro-Rhodesian Duncan Sandys from his Shadow Cabinet (a precursor to his better-remembered sacking of Enoch Powell in 1968), and he maintained Wilson’s snub to the Rhodesians.

Moreover, a few months before the General Election, some of the leading traditional Tory supporters of Smith resigned from the Anglo-Rhodesian Society – including its president Lord Salisbury. This was because Smith’s government had taken the further step of declaring a republic, i.e. no longer recognising the Queen as head of state. Lord Salisbury felt that he could not be seen as “condoning the decision of the Rhodesian Government to break their country’s last link with the Crown.”

It was perhaps no coincidence that this weakening of the old Tory establishment’s links with the Rhodesian lobby coincided with the National Front deciding to hold their own march to the Cenotaph, supporting the excluded Rhodesians and South Africans, rather than simply forming part of the crowd at the Anglo-Rhodesian Society’s event.

The NF was still relatively small in 1970 – it had fielded just ten candidates at that year’s General Election, with the party’s best result (5.6%) being achieved by a Baptist minister, Rev. Brian Green, in Islington North.

At the NF’s Remembrance Day march in 1971 the numbers grew to almost 1,000 and Rev. Green conducted the service, incorporating a prayer that not only mentioned Rhodesia and South Africa, but singled out the potential betrayal of Ulster which then as now (more than half a century later) was on mainstream politicians’ agenda.

By 1973 the NF was becoming a substantial political force, boosted by the successful parliamentary by-election campaigns of John Clifton in Uxbridge (8.2% in December 1972) and Martin Webster in West Bromwich (16.0% in May 1973), and more than 4,000 attended that year’s Remembrance Day march, rising to more than 5,000 in 1974, when Remembrance Day fell just a few weeks after the second General Election of that year.

In 1975 the Conservative Party elected a supposedly ‘rightwing’ leader – Margaret Thatcher, whose campaign team included several Monday Club MPs who had been supporters of the Anglo-Rhodesian Society. Yet soon after coming to power in 1979, Thatcher betrayed Rhodesia, effectively engineering the handover of the country to the Marxist terrorists of Robert Mugabe, who renamed the country Zimbabwe. Her betrayal of the Rhodesians was matched by her betrayal of White voters in the UK, who had foolishly believed that she would act on her hints about a stricter immigration policy.

By this time the NF had fallen from its 1970s pinnacle, and its Remembrance Day marches were never again to attract similar numbers. Yet the tradition is maintained by the current NF chairman Tony Martin and a small band of comrades, continuing an honourable tribute to the Empire’s war dead that dates back to the first betrayal of Rhodesia in 1966.

Editor’s note: The NF’s Remembrance Day parade of 1985 topped 2,000, including two drum corps and two colour parties (one all female). This was just before the final big split between what are now referred to as the Flag and Cadre factions. The 1986 parade at the height of the split went down to 1,500. The 1987 parade was banned by the Met Police after the Cadre faction (whose numbers were down to less than 50) refused to march with the Flag faction (who numbered around 800).