Late last night the Syrian ruler Bashar al-Assad fled Damascus, and seems now to have settled for a life in exile. The Ba’athist regime that has controlled Syria since 1963 collapsed.

Many H&D readers will mourn this development. Those who are obsessed by the threat of militant Islam will see the fall of Assad as a victory for Islamism, and to some extent it is.

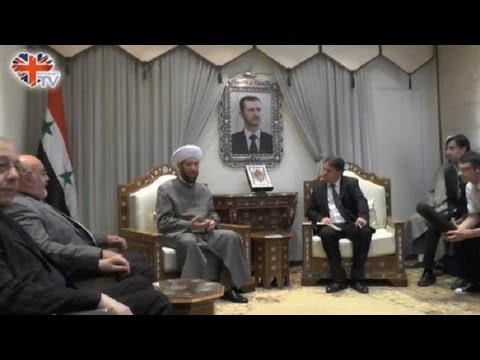

Assad, his father Hafez al-Assad (President of Syria for almost thirty years until his death in 2000), and their associates were part of one of Syria’s minority sects – the Alawites, a form of Shia Islam.

Alawites and other Shia account for only about 13% of the Syrian population, and they saw Assad’s rule as a bulwark against the Sunni majority, who are about 74% of Syrians – though of course that majority is itself divided among many internal factions, tendencies, and clan allegiances.

For many years the Ba’athists (including the Assad family) continued a policy that began under earlier regimes in the 1950s when Syria was allied to Nasser’s Egypt, of offering safe haven to national socialists. For a few years before the Ba’athist revolution, Syria and Egypt even formed a ‘United Arab Republic’, some of whose diplomats had secret links to national socialist dissidents in Western Europe (including the UK).

Yet at the same time, Syria became a close ally of the Soviet Union during the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras. This alliance continued during the fall of the Soviet bloc, and has been maintained by the neo-Stalinist Putin.

Inevitably therefore, Assad’s fall will be seen as a significant defeat for Putin, who has proved incapable of defending Russia’s oldest allies.

The Damascus-Moscow alliance which lasted for more than half a century under Stalin’s successors, and has now collapsed in chaos and ignominy, was a product of the failure of European empires in the mid-20th century.

In retrospect the one big chance that the Arab world had to unite against the nascent Israel state, was the ‘Greater Syria’ policy that was promoted by the postwar Labour government under Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin and a generation of anti-Zionist British diplomats and intelligence officers.

The defeat of that policy, and later attempts to recover British influence through secret alliances with our former enemies in the Middle East (the French and Israelis), led to the Suez debacle of 1956 and by extension to a generation of enmity between Britain and successive Syrian governments, culminating in the Assad alliance with Soviet communism and Putinist kleptocracy.

The sad details of these tangled affairs will be pored over by future generations of researchers and analysts. For now, all we can say for certain is that the Assad family and the entire Ba’athist era has been consigned to history.