Broadly as predicted, anti-immigration parties from what the media term the ‘far right’ have made big advances at the European Parliamentary elections – though the biggest winners overall were conservative parties; the ‘far right’ itself doesn’t exist as a coherent force; and the European Parliament has very limited powers.

[Please note that some of the statistics below might be altered very slightly as final checks are made to election counts. Ireland’s results are not yet available but we shall report on them later today.]

First the good news. In France, Marine Le Pen’s RN (successor to the National Front) was easily the largest party overnight with 31.4%, ahead of President Macron’s ‘centrist’ party on 14.6%, and the slowly recovering Socialists on 13.8%. The far-left party France Insoumise is now obviously in decline after several years as the leading force on the French left: they polled 9.9%. And France still has the weakest mainstream conservative party in Europe – the Republicans, who took just 7.2%.

France is one of the few European countries that has not just one but two electorally credible ‘far right’ parties. In fact until Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, it had seemed likely that the new Reconquête party led by the Jewish journalist Éric Zemmour and Marine Le Pen’s niece Marion Maréchal, would overtake Le Pen’s party. However, while Le Pen swiftly condemned Putin, Zemmour found it much more difficult to escape the electoral consequences of his earlier Putinism, and his party swiftly declined.

Reconquête are both harder line than RN against immigration (especially against Islam) and more traditionally conservative (in an Anglo-American, quasi-Thatcherite sense) on economic matters, while Le Pen has taken her party onto quasi-socialist turf and has become the natural leader of French workers.

This week Zemmour and Maréchal were (just about) able to celebrate. Together with the Greens, they just scraped over the 5% threshold and will have five MEPs, including both Maréchal and Zemmour’s partner Sarah Knafo.

Within hours of polls closing, President Macron called a snap general election. This will of course be a parliamentary not presidential election, since under the French system Macron will remain in office as President (and ultimately in control of foreign policy etc.) regardless of who becomes Prime Minister. But there is now a very real (though outside) possibility that Marine Le Pen will be Prime Minister of France within a few weeks.

While France continues to demonstrate the electoral toxicity of Putinism, it’s a very different story in Germany, where two blatantly pro-Moscow parties polled very well. AfD (Alternative for Germany) was originally a Thatcherite conservative party, but quickly became an anti-immigration party in opposition to the treachery of former Chancellor Angela Merkel.

This week, despite various scandals that have beset the party leadership with (for once) justified media exposés of their shady connections to both China and Russia, AfD polled 15.9% and overtook Chancellor Olof Scholz’s party SPD who fell to 13.9%. The mainstream conservative alliance CDU-CSU were easily the largest force with 30%, while the Greens (Scholz’s coalition partners) fell to 11.9%.

Very predictably the Homeland Party (which is the renamed NPD, Germany’s oldest surviving nationalist party) collapsed even further to a record low of 0.1% (27th of the 35 party lists, down among the joke and ego-trip parties). The good news is that the old NPD / Homeland is disappearing. The radical challenge to the corrupt AfD in future will come from the new party Dritte Weg, a party which stands for traditional nationalism, rejects Putinism, and is attracting growing numbers of young activists, though of course it didn’t contest the European election and is just at the stage of beginning to fight local and regional campaigns.

Another interesting development was the collapse of the Left Party (Die Linke, which was formed soon after the semi-reunification of Germany in the 1990s as an alliance of old communists and hardline socialists) to only 2.7%. Luckily for them Germany, unlike France, has no electoral threshold – so they will retain three MEPs, at least until 2029 when a new threshold system will be introduced.

Most of the old Left Party vote went to a new party created by one of their former leaders, the half-Iranian Sahra Wagenknecht, who is a long-term Russian asset and unsurprisingly shares AfD’s Putinism, while taking a Stalinist line in other policy areas.

Wagenknecht’s party polled 6.2% nationwide and was especially strong in parts of the former East Germany. In Thuringia, for example, AfD was the largest party with 30.7%, while Wagenknecht’s BSW polled 15%.

One consequence of AfD’s pro-Moscow stance is that it will have few friends in the new Parliament, having been shunned by most other anti-immigration / nationalist parties.

H&D will report further in the coming weeks and months on the reshaping of the European right.

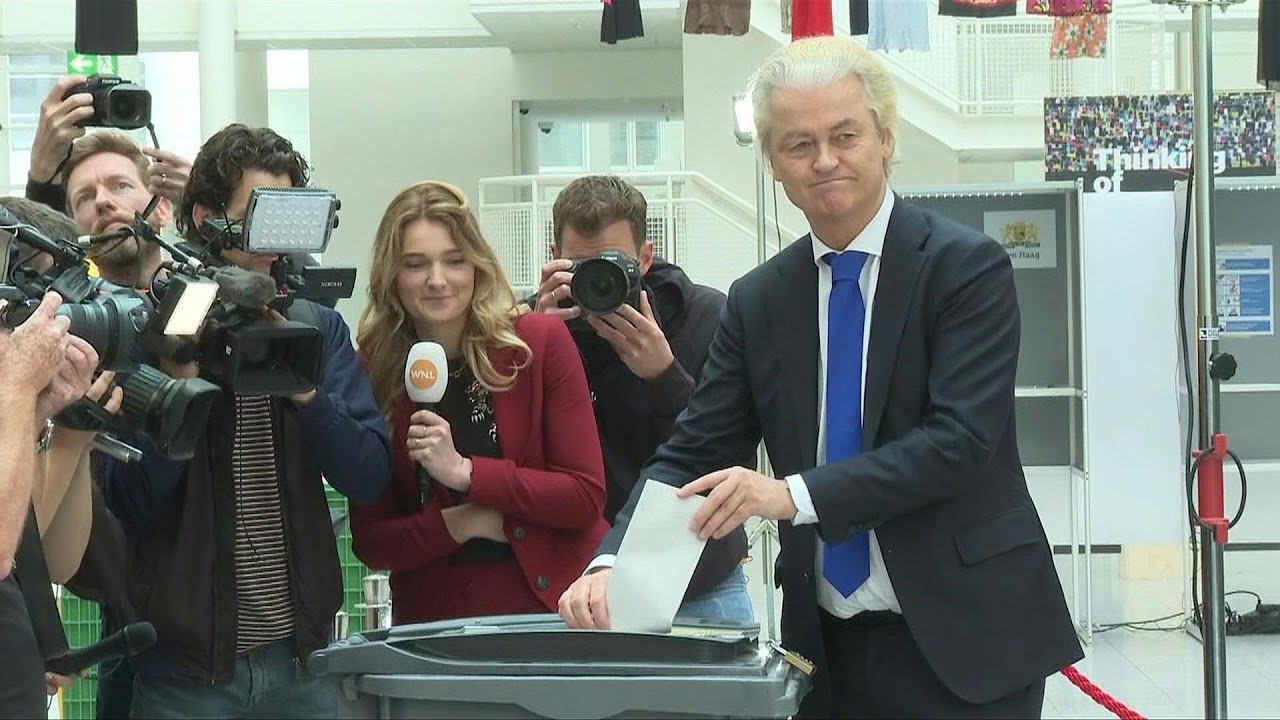

In the Netherlands, Marine Le Pen’s allies in the PVV (Freedom Party), led by Geert Wilders, finished second with 17.7%, a huge advance on its disappointing European election performance five years ago, though slightly down on their 23.5% in last year’s Dutch general election.

The rival Dutch nationalist party FvD (Forum for Democracy) whose leader Thierry Baudet once seemed a credible successor to Wilders as an anti-immigration leader but rapidly declined into fringe conspiracy theories and Putinism, collapsed from 11% to 2.5% and will no longer have any MEPs.

In Belgium, the Flemish nationalist Vlaams Belang (another important Le Pen ally) might have emerged the largest single party in one of Europe’s most politically fragmented countries, though final results are not yet clear. VB polled 13.9% but there were also big gains for the more ‘moderate’ Flemish nationalist/conservative party N-VA (New Flemish Alliance) who are only a fraction behind VB and in final results might yet overtake them.

Austria saw a historic success for another Le Pen ally, the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), who in a close three-way split have emerged as the largest party with 25.7%. Despite this victory, if they wish to be influential in the new Parliament they will have to watch their step on foreign policy, as Le Pen and her allies have indicated they will be utterly ruthless in expelling any party that discredits the anti-immigration cause by getting too close to Moscow.

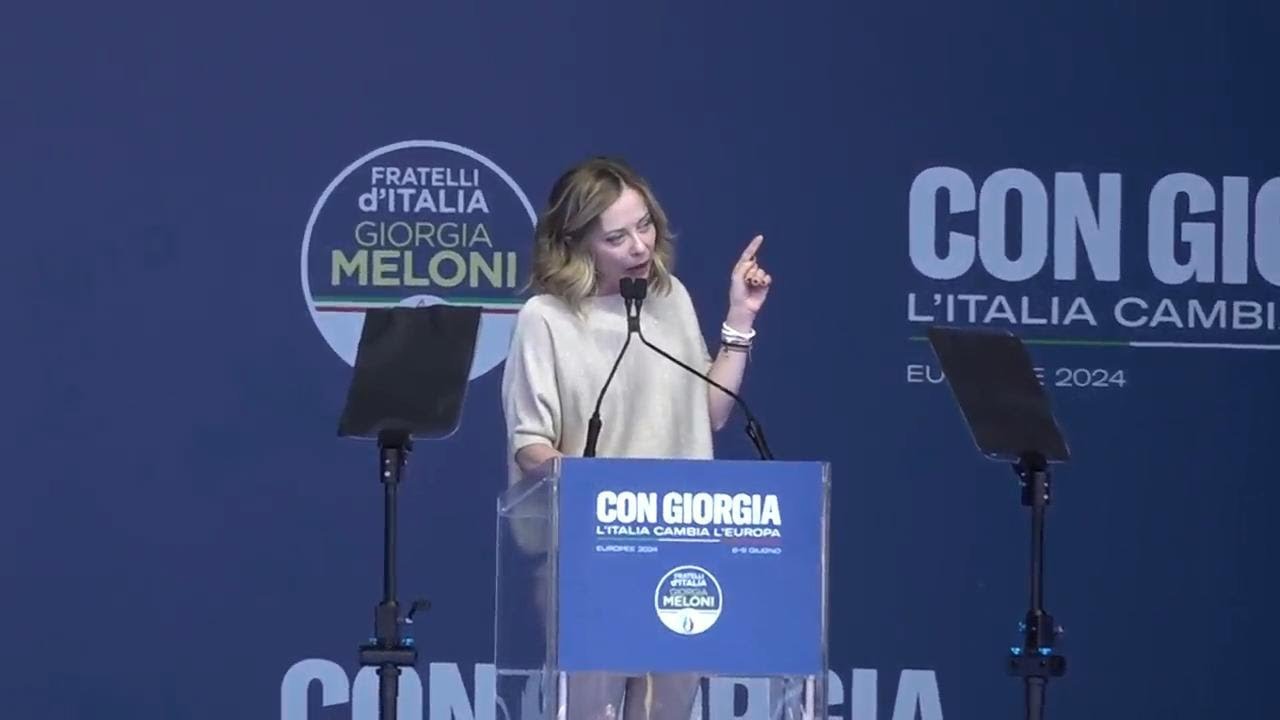

In Italy, Giorgia Meloni – the effective leader of the mainstream European right (i.e. of the block that stands to the right of conservatism and is at least nominally anti-immigration, while avoiding ‘racist’ or ‘fascist’ overtones) – had another election success. Her party ‘Brothers of Italy’ (Fratelli d’Italia) took 28.8%, ahead of the centre-left PD on 24%. A long-way behind these two were the once-successful but now declining anti-system protest party Five Star Movement on 10.0%, and then Meloni’s coalition partners Lega and Forza Italia, on 9.0% and 9.6% respectively.

Forza Italia is the remnant of the late Silvio Berlusconi’s reactionary conservative party, while Lega‘s leader Matteo Salvini was once the highest profile anti-immigration politician in Italy, but has long since been overshadowed by Meloni. Almost as much as Zemmour in France, Salvini has had to live down his former Putinism.

Meloni’s main political allies in the outgoing Parliament were the conservative-populist former governing party in Poland, Law and Justice. They lost power in last October’s Polish general election, and remained in second place yesterday with 35.7%, just behind the liberal/centrist slate ‘Civic Coalition’.

A rival Polish populist movement known as Confederation bounced back from several years of internal party conflict, polling 11.8% and gaining six MEPs. It’s not clear with whom they will ally in the new Parliament, as their political positions are anti-immigration, economically libertarian, and anti-Putin.

The strength of the anti-immigration right in the European Parliament will now depend to a large extent on whether Le Pen and Meloni can work together, or whether Europe’s conservative establishment manage to co-opt Meloni and some other quasi-nationalist parties.

Among the latter, one of the most widely publicised is in Spain whose reactionary conservative party Vox is a typical example of the trend towards pro-Israel, pro-capitalist stances among quasi-nationalist parties. Vox advanced from 6.2% (four MEPs) in 2019 to 9.6% (six MEPs) yesterday, barely justifying the hype it has been given in the media, but the big winners in Spain were the mainstream conservative PP, whose vote shot up from 20.2% to 34.2%.

Crank conspiracy theories embraced by some in our own movement were represented on Spanish ballot papers by a new party SALF (‘The Party is Over’), founded by an ideologically shallow social media celebrity, Alvise Pérez. A decade ago Peréz was a student in England at Leeds University, where he was active in the Liberal Democrats, and he later joined the Lib Dems’s short-lived Spanish equivalent Ciudadanos (Citizens).

His more recent success in building a political movement on the back of online conspiracy theorising and stunts, merely demonstrates the political idiocy of a large section of the ‘dissident’ movement, including the so-called ‘alt right’. Pérez’s party polled 4.6%, enough to gain three MEPs.

As usual the fringe right in Spain – a party that claims to represent the Falangist tradition – polled a tiny vote, amounting to just 0.05%.

In Portugal Vox’s imitator CHEGA (which translates as “Enough”, as in “We’ve had enough!”) polled 9.8%, up from 1.5% in 2019 when the party had only just been formed and was part of a hastily patched up joint ‘right-wing’ slate.

Croatia is one of several European countries where the broad right has reorganised itself in recent years. The largest party that represents traditional Croatian nationalist views is the Homeland Movement, who polled 8.8%, enough to elect one MEP.

Greece has seen some of the most blatant interference with ‘democratic’ politics. At the 2014 election, the national socialist party Golden Dawn polled 9.4% and elected three MEPs. This was one of several strong election results for Golden Dawn during the 2010s, but the party was subjected both to violent attack from left-wing terrorists, and to legalistic attack by the Greek state. As a result its leaders found themselves in jail and the party was effectively banned.

At yesterday’s election the main anti-immigration party was Greek Solution, though it’s a reactionary rather than national socialist party, and has expressed Putinist foreign policy positions. They polled 9.5% yesterday.

Cyprus has an anti-immigration party once seen as allied to Golden Dawn. This is the National Popular Front (ELAM): they polled 11.2% yesterday, up from 8.3% in 2019.

In Malta a national-socialist party allied to Golden Dawn – Imperium Europa, led by Norman Lowell – polled 3.2% in 2019. This year that fell slightly to 2.6%.

Among advances for anti-immigration parties, in Finland the Finns Party lost one of their seats, with their vote declining to 7.6% as voters rallied behind the government’s strongly anti-Moscow stance. To be fair, the Finns Party are also strongly anti-Putin, but in a country on the frontline at a time of crisis, there is a tendency to rally behind the government. In this respect Germany is the exception, because decades of brainwashing have taught Germans that they aren’t allowed to take a strong military stance against their enemies. Finnish patriots haven’t been emasculated.

In Sweden the main anti-immigration party Sweden Democrats polled 13.2%, very slightly down on their historic success in 2019.

Similarly in Denmark the Danish People’s Party fell slightly from 10.8% to 6.4%.

While some ‘mainstream’ anti-immigration parties can seem discreditable and cowardly, one of the most honourable and courageous of these parties is in Estonia, where the Conservative People’s Party (EKRE) advanced to 14.9%, from 12.7% in 2019.

In neighbouring Latvia the anti-immigration party National Alliance similarly advanced to 22.1%, from 16.5% five years ago.

For complicated geopolitical and historical reasons, the position in the third Baltic republic, Lithuania, is more nuanced. There, the largest of several ‘right-wing’ parties also represents the interests of ethnic Poles. (It should be remembered that during the 16th-17th centuries, during what we in the UK think of as the Elizabethean and Jacobean eras, the confederation Poland-Lithuania was one of the greatest powers in Europe.)

This Polish-Lithuanian party LLRA-KSS polled 5.8% this year, a fraction up from 2014. The rest of the Lithuanian ‘right’ is fragmented, with the National Alliance (a relatively new party founded in 2016), for example, polling 3.8%.

With most of the electorally credible ‘right’ (outside Germany) having moved against Putin, Hungary‘s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is in a delicate position. His party Fidesz remained easily the largest force at yesterday’s election, polling 44.3%, while the once-effective but now marginal nationalist party Jobbik managed only 1%. But it’s not yet clear with whom Fidesz‘s MEPs will ally in the new Parliament.

One of the few openly Putinist parties in the new Parliament is from Bulgaria, where the ‘Revival’ party polled 15.4%, a huge increase on their 1% in 2019 and reflecting the traditional instability of Bulgarian politics where wild swings of this kind are not uncommon. These Bulgarian Putinists are unlikely to find many allies in the new Parliament, unless AfD choose to go into the wilderness with them.

Romania‘s new populist ‘right-wing’ party AUR has adopted a softer form of Putinism, seeking to undermine Europe’s support for Ukraine without being blatantly pro-Moscow. As in much of South-Eastern Europe, the position is complicated by petty nationalism / chauvinism, with AUR for example promoting anti-Hungarian themes. (A lot of this is rooted in disputes going back to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the redrawing of Europe’s map following the First World War.)

AUR polled 15% but unlike the Bulgarian ‘Revival’ party it’s likely to moderate its stance on foreign policy, so as to remain part of one of the mainstream pan-nationalist or conservative groups in the new Parliament.

Slovakia‘s politics hit the headlines last month with the attempted assassination of Prime Minister Robert Fico, whose party Smer is difficult to place on the ideological map, being both left-wing and populist/’nationalist’. Smer was the second-largest party yesterday, polling 24.8%. As with the Romanian AUR, it might moderate its stance on the war in Ukraine so as to be admitted into one of the cross-party groups in the new Parliament, but since it was until recently in the same group as the UK Labour Party, it’s far from clear where it would naturally belong!

The more hardline nationalist party SNS (Slovak National Party), who back in 2014 were strong enough to elect an MEP), polled only 1.9% yesterday. Another Slovakian party, Freedom & Solidarity, represents a very different type of ‘right-wing'” socially libertarian, Eurosceptic, and ‘right-wing’ on economics in a US-style, pro-capitalist sense. They polled 4.9% yesterday.

Politics in the Czech Republic is another area that can mystify racial nationalist observers in other countries. The main anti-immigration party Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD – allied to Marine Le Pen’s RN, Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party, and other such forces in the European Parliament) is led by the quarter-Japanese, quarter-Korean, half-Czech, Tomio Okamura.

Last year one of their two MEPs, retired general Hynek Blaško, broke away to form a blatantly Putinist party but obtained a humiliating 0.5% yesterday. Meanwhile his former party fell to 5.7%, but will retain one MEP.

In Slovenia there is very little that could be termed a ‘nationalist’ party. The tiny Slovenian National Party split again a few years ago, and one of its activists founded a libertarian and anti-lockdown party ‘Resni.ca‘. They polled 4% yesterday, not enough to gain an MEP.

Luxembourg has no significant anti-immigration party, and its largest ‘right-wing’ force is a party that mainly represents the interests of pensioners, the mildly populist ADR, which polled 11.8% yesterday, enough to elect one MEP who will probably ally with Meloni’s ‘moderate’ nationalist group if it remains in its present form.

H&D will continue to monitor developments in Europe during the coming weeks, and will report on the reshaping of the electorally-focused side of European nationalism both here and in future editions of the magazine.