Editor’s note: This review (by our assistant editor Peter Rushton) originally appeared in two parts, in issues 120 and 121 of H&D (July-August 2024 and September-October 2024).

This review is also now available in Spanish – Esta reseña ahora también está disponible en español

Léon Degrelle in Exile (1945-1994) – by José Luis Jerez Riesco, published by Antelope Hill Publishing, softback, 2022, 518 pages, ISBN -9781956887167, available from Antelope Hill Publishing, 526 N. Saint Cloud Street, PMB 307, Allentown, PA 18104, USA, or online from – www.antelopehillpublishing.com – for $29.89.

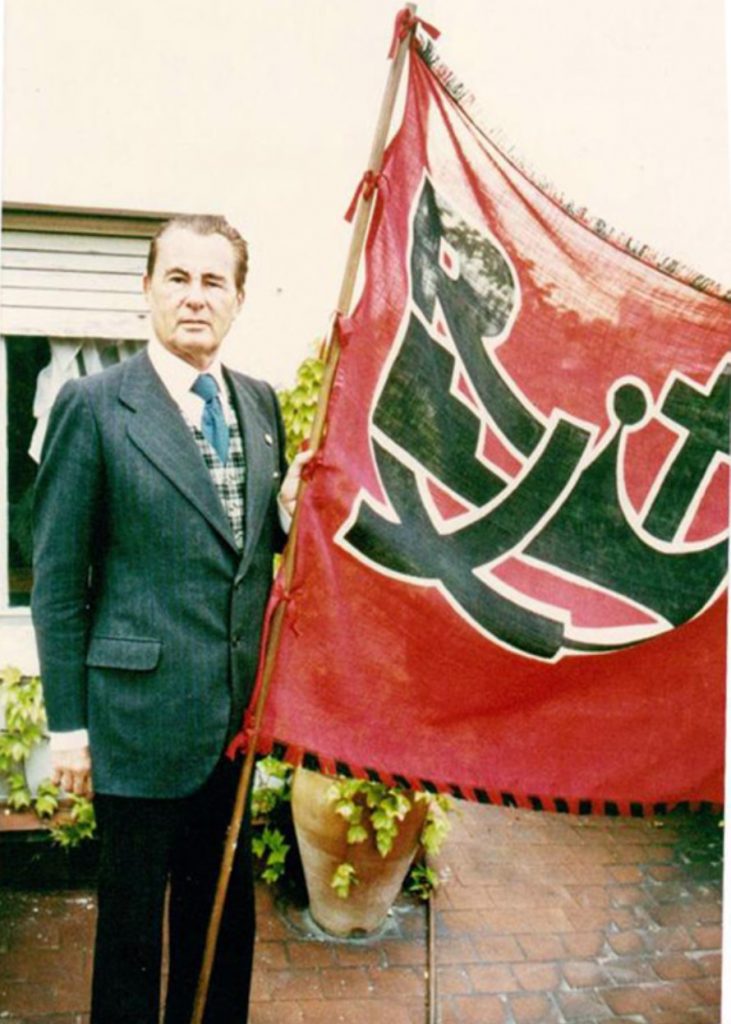

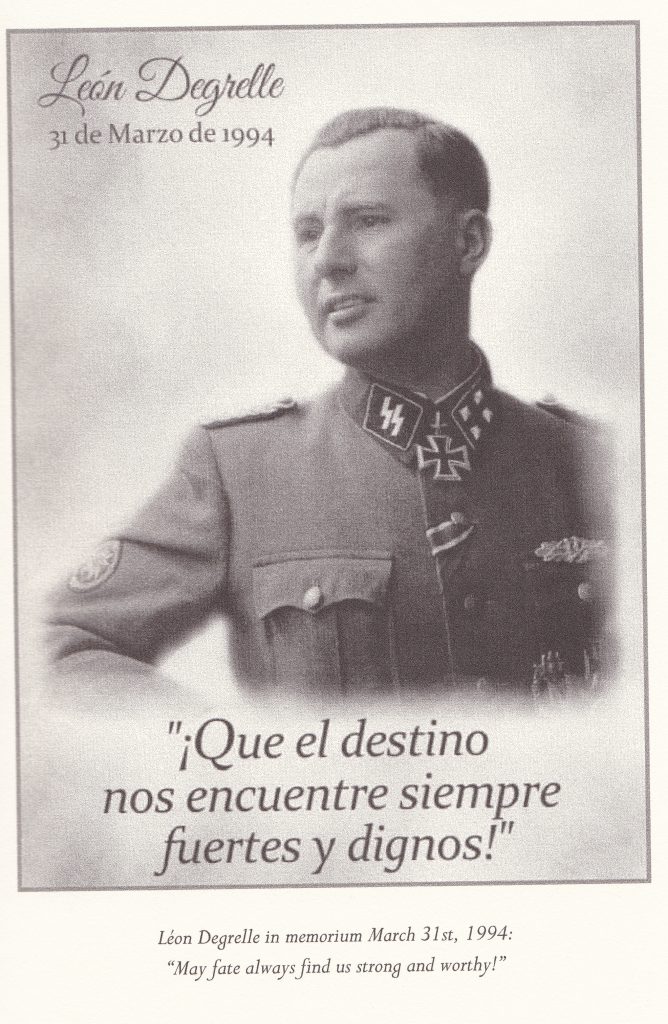

Just over thirty years ago, on 31st March 1994, Léon Degrelle died in Malaga aged 87. He had been admitted to hospital three weeks earlier, but right up to that point had been an active writer and campaigner for national socialism, the cause to which he dedicated his life. By the time of Adolf Hitler’s centenary in 1989, Degrelle was the most important national socialist still alive, and there is a strong case for arguing that he was the most important and active national socialist of the post-war era.

As this remarkable biography (first published in Spanish in 2009 and now translated into fluent and highly readable English) records, Degrelle wrote a poignant letter just a few weeks before his death, to his comrades of half a century earlier, those who had fought under his command at the battle of Cherkassy Pocket in January-February 1944.

“My dear comrades! Confined in the depths of my exile, I have never been closer to you than on this 50th anniversary of Cherkassy.

“Those days, by dint of courage, renunciation, and sacrifice, you delivered the last great victory in the east to the armies of the new Europe. Remember with pride, in today’s rotten world, only the virtues of heroes still shine.”

Though this book deals with the post-war years, I should briefly summarise the path that led Léon Degrelle to his wartime heroism. Born into a Catholic conservative family of French-speaking Belgians (in fact his father had moved to Belgium from France), Degrelle became a political journalist in the late 1920s. During 1932-33 (aged 26) Degrelle used his journalistic and publishing activities to radicalise Catholic conservatives, forming the Rexist Party in 1935. At the 1936 elections – before his 30th birthday – he led the Rexists to a significant breakthrough, polling 11.5% and gaining 21 parliamentary seats.

These advances coincided with the rapid rise of the Falangist Party in Spain, and Degrelle was one of the leading international allies of the Falange’s founder, José Antonio Primo de Rivera. He received membership card number one in the Falange’s international organisation.

Though José Antonio was captured by communists before the start of the Civil War, and was infamously murdered in a prison yard in Alicante in November 1936, Degrelle remained close to the martyred leader’s comrades – a fact that helped save his life on more than one occasion after 1945.

Building links with both the German and Italian governments, Degrelle used his journalistic and rhetorical skills to expose corruption within mainstream Belgian politics, but was opposed by influential reactionaries both in politics and in the Catholic church (in very similar fashion to the attempts by Spanish reactionaries then and since to marginalise and divide Falangists).

After two months in prison amid the chaos of May-July 1940, Degrelle sought to rebuild the Rexist Party and to convince his comrades to set aside petty nationalism in favour of a wholehearted alliance with the new European order of national socialism. This took on a new dimension in June 1941 when German forces invaded the Soviet Union, and the Second World War, on the Eastern Front at any rate, took on the character of an anti-Bolshevik crusade.

Degrelle created the Légion Wallonie (Walloon Legion) – recruiting anti-communist French-speaking Belgians to fight alongside the German Army. At first assigned to operations against Russian partisans operating behind the advancing German lines, the Legion was sent into frontline combat against the Red Army from February 1942 and quickly distinguished itself by exceptional valour against a brutal foe.

In 1942 Degrelle was awarded the Iron Cross, First Class, and went on to receive further medals during the next three years. As a logical development of this European alliance of political soldiers, Degrelle’s forces were incorporated into the Waffen-SS in 1943 as the SS-Sturmbrigade Wallonien.

By January 1944 Degrelle’s Legion had a fighting strength of 2,000 and was thrown into some of the harshest combat of the entire war, encircled by Stalin’s Red Army near what is now the central Ukrainian city of Cherkasy. During several weeks of heroic defence until breaking out of the “Cherkassy pocket”, well over half of Degrelle’s Legion were killed, captured or wounded.

Hitler awarded Degrelle the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, and a few months later after further heroic fighting in Estonia he received the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, one of only eight non-Germans ever to obtain this award. During late summer 1944 Degrelle rebuilt his Legion with further Belgian recruits, supplemented by Spanish Falangists – survivors of the División Azul (Blue Division) who had opted to remain on the Eastern Front, fighting against the Soviet hordes even after their official withdrawal by General Franco’s Madrid government the previous autumn.

By this time, it was clear that only one thing could save Germany from defeat: a recognition by the West that their alliance with Stalin would give the Kremlin control over half of Europe, and a consequent reversal of Western policy. The SS leader Heinrich Himmler pursued several avenues, sadly without success and eventually leading to his own murder on 23rd May 1945 by sinister forces determined to distort history for their own ends.

For the bravest of the brave among the Waffen-SS and Wehrmacht, all they could do was fight to the last man, while women and children desperately fled westward to evade Stalin’s advancing barbarians. In April 1945 Degrelle’s Legion was again smashed defending the last line that could be held east of Berlin, the Oder and Neisse rivers.

Even now, with the Reich’s defeat imminent, Degrelle refused to give in. The first pages of this book find him in Oslo, again trying to rebuild a fighting force of committed national socialists. Hearing of the German surrender on 7th May 1945, his first reaction was to seek some way to get to Japan and continue the struggle. (In common with almost everyone on both sides, Degrelle believed that Japan would remain in the war for at least another couple of years. Naturally, he was unaware of the existence of the nuclear bomb that would defeat Japan only three months later.)

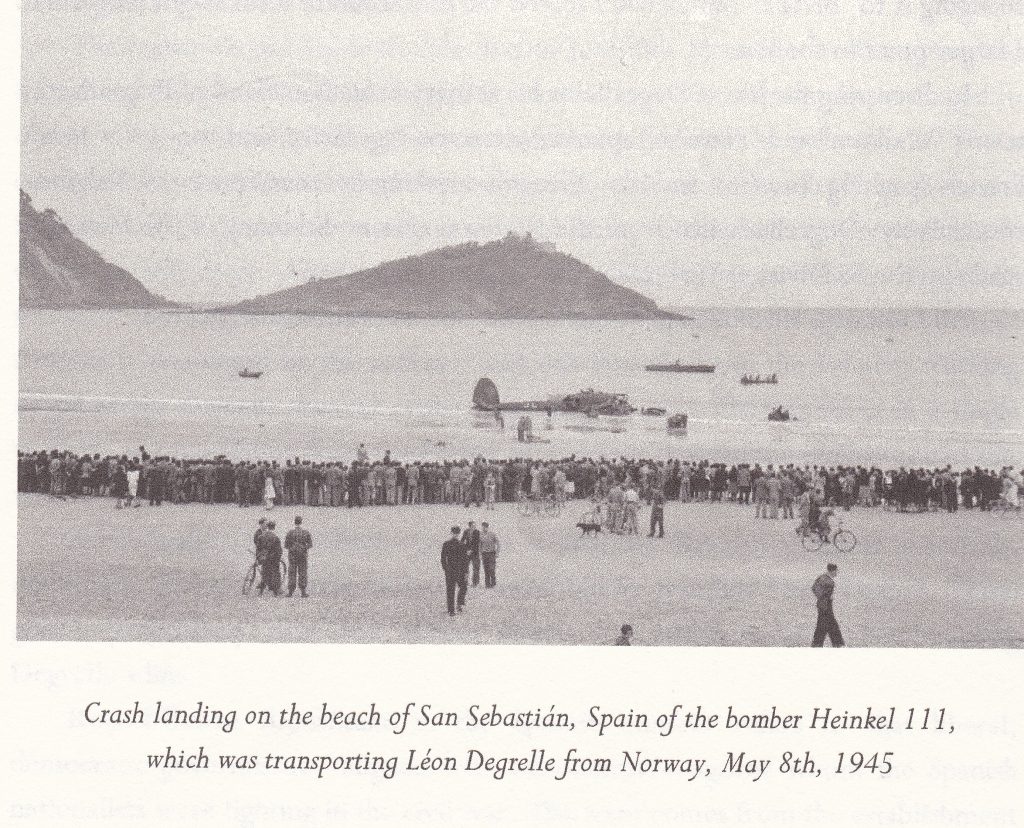

Unwilling either to surrender or even to disguise himself, Degrelle put on his uniform and medals, crossed Oslo, and boarded a plane belonging to Reich minister Albert Speer (who was back in Germany serving in the transitional Flensburg government and was soon to be arrested and jailed at Nuremberg and Spandau).

The book opens with a breathtaking account of Degrelle and his five comrades flying through the night of what we now call VE Day, then crash landing on a beach in northern Spain. Severe injuries suffered during this crash landing probably helped save Degrelle’s life. There were forces within Franco’s government who would happily have betrayed him (just as they betrayed the British national socialist John Amery by conveniently finding that on a technicality his application for Spanish citizenship had not been rubber-stamped, thus condemning him to the gallows in London for treason).

As this book explains, however, there were other forces in the Franco and post-Franco years who maintained loyalty to Falangism and were able to protect Degrelle, though his fate remained in the balance. Some of the most interesting revelations in this book concern repeated attempts even under the Franco regime to secure Degrelle’s extradition to Belgium, where he would certainly have faced execution.

In 1969-70 for example, one of the most serious attempts to obtain extradition was plotted between members of the Belgian and Spanish governments who shared membership in a reactionary Catholic society, Opus Dei. Leftwing and liberal journalists around the world have sometimes criticised Opus Dei as though it were somehow ‘fascist’, but as this book explains, reactionary networks of this kind, embedded in conservative parties worldwide and in global capitalist institutions, are a greater enemy of national socialism than of the now defunct classical Marxism.

Part of the leverage that Belgian politicians used with the Spanish was the prospect of admitting Spain to the Common Market / EEC. Spanish politicians agreed to expel Degrelle from their territory so that he could be arrested elsewhere, since technically it was not possible to extradite someone from Spain for political offences. During early 1970 Degrelle had to rely on political allies to hide him at various addresses in Spain so as to prevent this expulsion being carried out.

His immediate family were not so fortunate. Letters quoted in this book reveal the searing pain – far worse than physical wounds sustained in battle or in his near-fatal plane crash – that Degrelle suffered in the immediate post-war years when his aged parents were imprisoned in Belgium, spending their dying years incarcerated, while his wife attempted to take refuge in Switzerland, but was handed over to the Belgian authorities and given a ten year jail sentence (eventually released on health grounds after more than five years). Their young children were interned at a “juvenile correction centre” and for some time Degrelle was unable to learn anything about their fate.

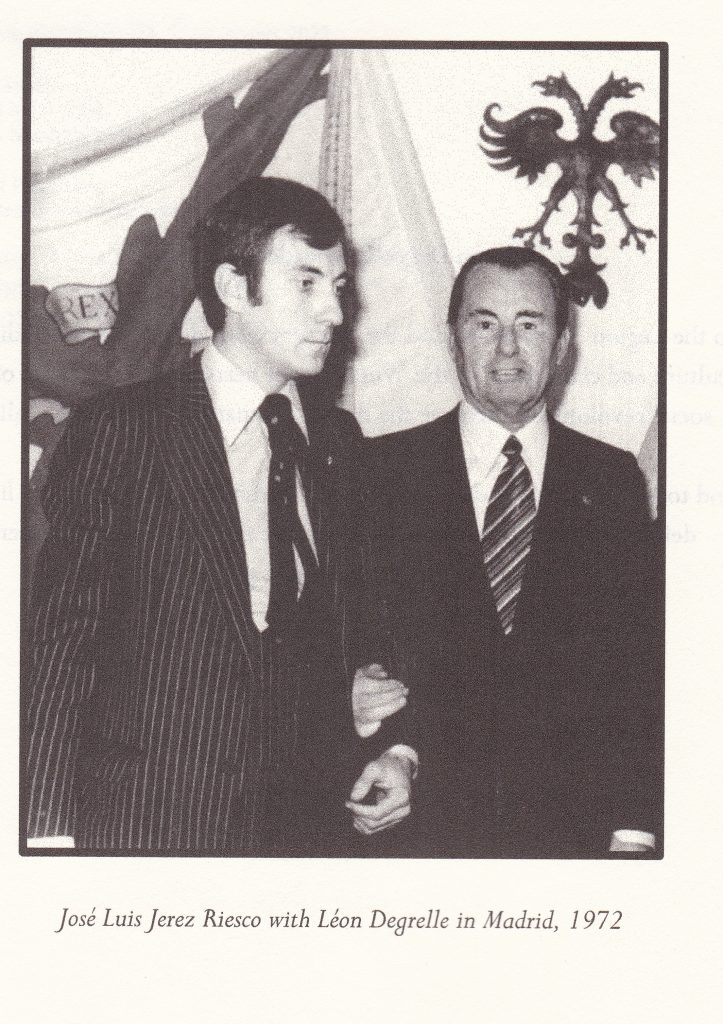

This biography, by its subject’s friend and political comrade José Luis Jerez Riesco, himself a dedicated national socialist as well as a lawyer and historian, focuses on the last 49 years of Degrelle’s life. Years spent in exile, but by great good fortune exiled in Spain, the nation which more than any other postwar maintained a high-level intellectual and cultural tradition of national socialism and where organisations such as CEDADE and more recently Devenir Europeo have passed on the torch to new generations.

As this book makes clear, Degrelle himself played a major role in this process and I have no doubt that he would wish to be remembered as much for being an ideological custodian of Hitlerian ideals, and for inspiring the young, as for his personal courage on the battlefields of the Eastern Front.

In fact, the abiding impression of Degrelle in Exile is of a man who remained forever energetic and hopeful that the 1945 disaster would be reversed. Some of his final writings looked back to his days as a campaigning journalist in pre-war Belgium and highlighted the fact that he had been the model for the cartoon character Tintin, the adventurous young journalist hero, drawn by Degrelle’s pre-war colleague Hergé.

For Degrelle national socialism was not a form of German nationalism, not merely a way to restore the living standards of the German people, to undo the injustice of Versailles, and to rescue Germans from the rapacity of the evil twins capitalism and communism. It was far more than that: it was the ultimate ideological embodiment of European civilisation.

Speaking in 1981 on the theme “What is Europe?”, Degrelle told a CEDADE audience:

“We almost know Europe before we know our own homelands. Where did Europe emerge from? She emerged from those first peoples of the Mediterranean who have created the culture of Europe, the political order of Europe, their civilization.

“One day, I said to Hitler, I asked him, ‘What is your country? Who are you?’ He answered me, ‘I am Greek,’ and he was right. It is Greece who has given us all our spiritual life.

“If the European world exists, if it makes sense, it is because two thousand five hundred years ago, this small country, Greece, with few inhabitants and little wealth, was able to forge the supreme wealth that is civilization.”

This same restless intellectual energy led Degrelle to pursue historical justice for the Third Reich. He was not content to live out a comfortable exile, and believed honour required him to fight for the truth. In the immediate postwar period this led him to pursue a version of the argument against “victors’ justice” that had also been put in London by Lord Hankey (formerly Sir Maurice Hankey) the leading civil servant of the pre-war British Empire.

In the autumn of 1946, Degrelle wrote to the Secretary-General of the nascent United Nations, the Norwegian trade unionist Trygve Lie. It’s most unlikely that Lie would have viewed these arguments favourably, since he was such a devoted Zionist that he leaked sensitive secrets to Israeli leaders. But almost eighty years later, it is helpful for Degrelle’s case to be read by new generations of readers. In one section of the letter, he asked the UN to consider:

“Is Losing Sufficient to be Considered Wrong? We lost. This is obvious. Is it enough to have lost to be wrong? Germany might well have won the war, not only in 1940, but even much later.

“If the new weapons of the Reich had come out in time, if Hitler had definitively ensured the unification of the European continent, then our political lucidity and our soldiers’ self-denial would have been glorified! Fighting as equals on the front, in suffering and in glory, we would have been able, on behalf of our people, to speak as equals to the German victors when it came to the reorganization of Europe.

“Other Belgians, other Frenchmen, other Europeans had bet on the Allies’ victory, and wore Allied uniforms in the RAF and in commando units. Patriotism just as vibrant as ours, so we would like to believe, had led them to their decision. Would they have been considered and automatically labelled miserable traitors if the fate of the war had turned out differently than they had anticipated?

“Let us be sensible and frank. There were idealists on both sides. The result of the war, a purely material result, has elevated one side to the clouds and thrown the other to the ground. The opposite could also have occurred: the Reich could have invented the atomic bomb first; Hitler could have reigned over the ruins instead of Mr Churchill.

“The question, therefore, is not whether some have collaborated with the Reich, victor in 1940 (the ‘bad guys’), or whether others have collaborated with Mr Churchill, candidate-winner of 1944 (the ‘good guys’), but if the motivation for these collaborations was clean, selfless, free from any pre-war ties, vigilant for Europe, stimulated only by passionate love for the homeland, and love for thy neighbour.

“All post-war political processes have ignored this essential consideration. That is why everyone is misrepresented and will be reviewed one day, whether by courts more sensitive to the law, or by history, the true court of men, of states, and of nations.”

By 1979 Degrelle was putting his case for historical justice in rather different terms. In 1946 the main accusation against the Axis was of having pursued a criminally aggressive war of conquest, and Degrelle thus focused his case on arguing that in most respects the soldiers on each side were motivated by patriotism: ‘war crimes’ were merely another version of the Latin motto vae victis, ‘woe to the defeated’.

But by the end of the 1970s it was obvious that the Third Reich was no longer seen simply as a military foe to be ground into the dust in order to prevent another German military revival. A pseudo-religion of Holocaustianity was now developing, that had corrupted even the Vatican itself. Even though his position in Spain might now be under threat, thanks to Franco’s death and the transition to ‘democracy‘ under the 1978 Constitution, Degrelle believed it was his duty to expose the lies on which the Holocaustian cult had been built.

On 20th May 1979 he wrote to the new Polish Pope John Paul II asking him frankly whether as a young Pole affiliated to the anti-German resistance, he had ever personally seen the slightest evidence to support the fables of mass gassing. Degrelle acknowledged:

“People certainly suffered in Auschwitz, as in other places too. All wars are cruel. The hundreds of thousands of women and children who were atrociously burned alive—by direct order of the Allied Heads of State—in Dresden, Hamburg, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki, experienced far more horrible suffering than those who were interned as political deportees, resistance (these two categories were 25 percent of the total population of the camps), conscientious objectors, sexual deviants, or common criminals (75 percent of the camp population), and sometimes died, in the concentration camps of the Third Reich.”

He pointed out the scientific implausibility of the official version, and the lack of documentary evidence for the alleged ‘Holocaust’ – a striking absence of evidence that continues in 2024:

“Most Holy Father, as far as a formal policy of genocide is concerned, no document has been able to provide the least official proof of this for more than thirty years, especially as regards the alleged cremation at Auschwitz of millions of Jews. The claims launched and constantly repeated for so many years, in a fabulous campaign, cannot stand up to serious scientific examination.”

CEDADE republished Degrelle’s letter with additional material later the same year, in which the author drew attention to recent analyses by the revisionist scholars Arthur Butz and Robert Faurisson.

Meanwhile the infamous Hollywood miniseries Holocaust had been shown on Spanish television but (unlike most of Europe) Spain still had a relatively free press that was prepared to publish comments about the series and related historical arguments, from all sides. Degrelle gave his reaction to the newspaper El Imparcial, which included these paragraphs that certainly would not be published by any mainstream European newspaper today:

“Without going as far as Illinois [to interview Arthur Butz], Spanish Television could have invited at least another great specialist, also a professor, Professor Robert Faurisson, from the French University of Lyon. This gentleman is also not a Nazi. He is an anti-nazi who personally shocked me by welcoming the assassination of Marshal Pétain’s minister Philippe Henriot in June 1944. That is to say, he is nothing of a Hitlerite.

“Professor Faurisson was, in his position, dedicated to the study and analysis of texts and documents. This is how, as an exclusively intellectual project, he and his students happened to study documents on a well-defined problem: gas chambers and Zyklon B gas. Over time, Professor Faurisson had his doubts and checked the ‘dossier,’ made numerous visits to the German archives, consulted all the specialists, made two visits to the Auschwitz camp, etc. Fourteen years of intense, strictly intellectual work on this sole problem!

“His scientific conclusions finally appeared in the form of letters to the well-known daily Le Monde, as well as in studies collected in other publications. Faurisson points out that the use of Zyklon B gas, in order to carry out extermination, contrary to the claim in a thousand books and in Holocaust, is a technical impossibility. This extremely dangerous and flammable gas would not have allowed the corpses to be handled for twenty-one hours. Professor Faurisson has studied every detail of the gas chamber that is shown to visitors to Auschwitz: it is fake, built after the war. The French sage finishes his study categorically: this whole story of gas chambers is insane; it is only a myth.

“The thesis of Professor Faurisson has had such a profound impact that Switzerland’s Italian-language television invited him to participate in a debate that preceded the Swiss broadcast of Holocaust. Why, with Lyon only two hours by plane from Madrid, did TVE not invite Professor Faurisson like the Swiss did? Possibly because his participation, strictly scientific in nature, had a considerable impact in Switzerland.

“TVE did not accept my testimony either. I have known Hitler and Himmler up close. I could explain many things. I have publicly offered to participate in TVE’s discussions and have kindly reiterated my offer in writing.

“They should have allowed historians, learned men, witnesses from both sides, to appear in a gentlemanly way before a public capable of judging for themselves and not have deceived them with a prefabricated, unilateral debate.”

The very fact that Degrelle was determined to continue his fight for historical justice made international Jewry determined to silence him. Once it had become clear that political chicanery would fail and that honourable Falangists in Spain would prevent his extradition, they turned to gangster methods.

This book gives fascinating details about the most serious plot against Degrelle in 1961. I am grateful to its author for having provided important context that allowed me to assess facts that have emerged very recently about this episode. Jews and ‘anti-fascists’ were angered by their failure to force the Spanish Government to surrender Degrelle for a show trial. They became even more incensed when rather than retreating into obscurity, Degrelle continued to be an outspoken national socialist and supporter of worldwide political networks defending Adolf Hitler’s political legacy.

In 1961 Zionist agents decided it was time to act against Degrelle. At first, they planned to take him to Israel, but the plan was later amended. Instead they would torture and interrogate him on a yacht off the Spanish coast, then they would take him to Belgium, where the postwar government had already sentenced him to death. The true story of this conspiracy has been deliberately obscured for more than sixty years, but in March 2024 a BBC broadcast (while only referring to Degrelle tangentially as part of a quite different story) exposed part of the truth, and careful study of this book enabled me to track down further details.

“Victory has a hundred fathers, but defeat is an orphan,” is a proverb often attributed to President Kennedy. In reality it was first stated by Mussolini’s foreign minister and son-in-law Count Ciano. Regardless of its origins, the proverb is certainly applicable to Israel’s intelligence service Mossad and its ‘nazi-hunting’ operations.

When a Mossad team kidnapped Adolf Eichmann from Argentina in May 1960, Israel was happy to take the credit. Eichmann’s show trial in Jerusalem was (in true Stalinist fashion) celebrated as ‘evidence’ of the ‘Holocaust’, which in the early 1960s was just beginning to be transformed from a disputed and marginal aspect of Second World War history into what it has become in the 2020s – an unchallengeable holy writ. But when – almost exactly a year after the Eichmann kidnapping – a similar operation was attempted against Léon Degrelle, the ignominious failure of this conspiracy meant it had to be dismissed as the work of ‘amateurs’, entirely disowned by Israel.

The conspiracy’s ringleader, journalist Zvi Aldouby, received most opprobrium. Within days of his arrest and the collapse of his plan to kidnap Degrelle, Aldouby was condemned by fellow Jews, including some who had worked with him in the plot. Recent authors such as Guy Walters have believed and repeated Israeli disinformation, but closer examination of the facts suggests that this was an exercise in the traditional intelligence game of “plausible deniability”.

The man later known as Zvi or Zwy Aldouby was born Herbert Dubinsky in 1931. Having immigrated to Palestine with his family, the teenage Dubinsky was a volunteer with the Haganah, the paramilitary wing of the Jewish Agency fighting against the British Mandate. After the State of Israel was declared in 1948, he joined the Haganah’s elite spearhead – Palmach – terrorising Palestinian civilians and fighting against Arab armies.

Having worked in a field intelligence and reconnaissance role for Palmach, Dubinsky joined the Shin Bet security and intelligence service in 1949, transferring to the Israeli Foreign Office in 1951, and it was at this point he was advised to change his name from Dubinsky to Aldouby. (This could be understood as either a Hebrew or an Arab name, and was therefore suitable for a covert operative.)

From 1952 to 1957 the young Aldouby worked as a journalist for the Haboker newspaper (associated with the conservative opposition party in Israel) and for the official Army journal Bamahaneh. After moving to New York in 1957 he continued working as Bamahaneh’s US correspondent, travelling around the US and visiting Army bases. Later this allowed him to insist that he had ceased to have any official Israeli role as early as 1952, but certain aspects of his work imply that he continued to perform a propaganda and intelligence function.

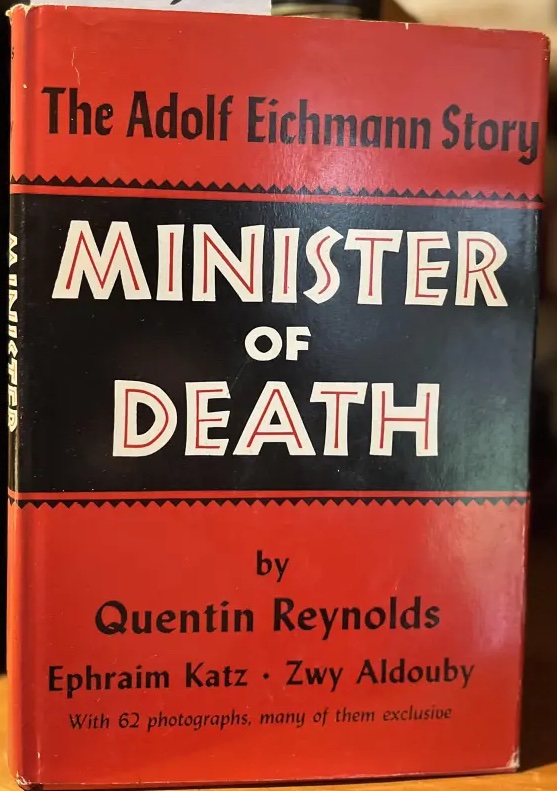

During 1957-60 Aldouby studied journalism at Columbia University, from which he was supposedly expelled for a “poor academic record” in the spring of 1960. Coincidentally or not, this was at precisely the same time as the Eichmann kidnapping. Aldouby quickly combined with fellow-Israeli Ephraim Katz to produce articles about the Eichmann case for the American magazine Look and the German magazine Stern.

Look magazine’s founder and editor Mike Cowles had a longstanding relationship with the CIA. Aldouby and Katz were put in touch with Quentin Reynolds, an American journalist with long experience of propaganda work. Their articles about Eichmann were expanded into a book – Minister of Death, co-authored by Reynolds.

After the collapse of the Degrelle kidnapping plot, Aldouby was quickly painted as a mere opportunist who had jumped on the Eichmann bandwagon to make money. Yet the choice of Quentin Reynolds as his co-author is strong evidence that Aldouby was actually a trusted Israeli propaganda and intelligence asset from the start. As I have explained in an online article for the Real History blog, Quentin Reynolds had a significant role for many years as a leading propagandist for Jewish and ‘anti-nazi’ causes. This included work for the anti-British terrorist group Irgun.

It’s also highly significant that as part of his work on the Eichmann story, Aldouby obtained partial transcripts of interviews between Eichmann and Willem Sassen. These interviews (and other highly dubious ‘confessions’ by Eichmann) are a complicated subject requiring analysis in a later article. But for the purpose of this review, the important thing is that Aldouby himself was one of the first people to obtain the Sassen transcripts, which sixty years later have been deployed as ‘evidence’ for the official ‘Holocaust’ narrative.

Following his work on the Eichmann story, Aldouby travelled to Israel and Europe carrying out further research and planning the Degrelle kidnapping. This time his right-hand man was an older Israeli also resident in New York, Yigal Mossinson. Like Aldouby, Mossinson was a veteran of the Palmach. He had for a time been interned by the British mandate authorities for Zionist terrorist activities. During the 1950s he was sent by Mossad to operate under journalistic cover in New York.

Aldouby and Mossinson sailed across the Atlantic to Le Havre, then spent several weeks in Paris meeting with fellow conspirators, mostly Jews and Spanish leftwing exiles. Mossinson travelled ahead to make preparations for a yacht that would smuggle the kidnapped Degrelle out of Spain.

Aldouby and a young Parisian Jew, Jacques Feinsohn, drove through France and crossed the Pyrenees. But instead of being able to proceed with their plot, they were arrested soon after entering Spain on 3rd July 1961. Officers of the Guardia Civil took them into custody, after discovering weapons and incriminating documents in their car.

What had gone wrong for the supposedly ultra-efficient Mossad? As early as 14th April, seven weeks before the arrests, the CIA’s Madrid station received information from one of their contacts inside the Spanish intelligence service. At about the same time, Spain’s Director General of Security, Carlos Arias Navarro, warned Degrelle that Jews were planning to kidnap him.

It’s clear that the CIA’s information came from Arias’s office, and amounted to the same story. While they didn’t yet know the names of those involved or the specifics of what was planned, the report read as follows:

“The Jews have been planning the kidnap of Leon Degrelle. They plan to abduct him in the same manner by which Eichmann was abducted in Buenos Aires and with the intention of making him appear in the trial of Eichmann in Tel Aviv. It appears they are trying to abduct ex-Nazi chiefs in a spectacular manner for political and vindictive purposes.

“The plotters of the kidnapping of Degrelle belong to the Israeli Secret Service and have been personally in contact, or at least have had contact, with a group of Jews in Hamburg who influence the German magazine Stern; and according to what is said, they plan to abduct Degrelle with a plane, exactly like they did with Eichmann. In the Eichmann operation they counted on Soviet collaboration; Russian agents were the ones who identified and discovered the true identity of Eichmann.”

This is itself a highly significant comment that we should pause and consider. By 1960, in theory, international Zionism and Soviet Communism were at loggerheads. Yet this report (perhaps originating with Spanish intelligence but entered without demur into the CIA’s file on the case) states that Mossad’s kidnapping of Adolf Eichmann was carried out with “Soviet collaboration”. In other words – just like the ‘evidence’ of homicidal ‘gas chambers’ at Auschwitz which came from a Soviet commission – the most famous postwar capture and trial of a ‘war criminal’ involved the KGB.

“It is also said that the Jewish agents are trying to locate and detain other Nazi leaders like Bormann in order to abduct them. It is advisable that Degrelle be watched and guarded, above all during the period of the Eichmann trial.

“The Israeli operation consists in carrying out sensational abductions, like that of Eichmann, in order to fulfil their vengeance, to get the most out of propaganda, and to complicate by any way possible the international relations and the internal politics of certain countries.”

The report went on to speculate that the kidnap plot might be linked to the mysterious activities of the head of the Belgian security service, Paul Woot de Trixhe, whose son Jacques had recently been working for the electronics company Philco on contracts at a US military base close to Degrelle’s home near Constantina, about 70 km from Seville.

It’s possible to infer from the CIA files that one reason for the Degrelle kidnap plot failing is that 1961 was the height of the Cold War. Intelligence agencies even within the Western side were sometimes at odds with each other. In particular, the West German intelligence service BND was run by Gen. Reinhard Gehlen, former head of the Third Reich’s military intelligence on the Eastern Front.

In Degrelle in Exile, José Luis Jerez explains that in addition to his information from Spanish security chief Arias, Degrelle was tipped off by two sources who had close links to Gehlen’s BND: the Count of Mayalde, former Spanish Ambassador to Berlin and by this time Mayor of Madrid, who had been in charge of Franco’s security service just after the Civil War; and Horia Sima, exiled commander of the Romanian Iron Guard.

For almost three months during April, May and June 1961, Degrelle took the advice of his friends in the Spanish security services (and other friends with connections to national socialists still serving in West German intelligence) and stayed away from his home, remaining under close guard in a small apartment in Madrid.

But in the absence of definite information, he decided to return to his estate at La Carlina, near Constantina. And shortly before his return, Degrelle started to get clearer information from his national socialist comrade François Genoud. In his letter, Genoud warned Degrelle that he had by chance discovered details of a kidnap plot against him similar to the Eichmann conspiracy. There are slightly different versions as to how Genoud became aware of the plot, but one possibility is that Mossad had set out to create an elaborate ‘false flag’.

During the first months of 1961, Aldouby travelled in Israel and Europe building his network and compiling information. In Switzerland he presented himself as an Arab-American and used a non-Jewish variant of his name – Herbert Aldouby. Together with a young Moroccan Jewess and fellow Mossad officer, Barbara Aigon, he introduced himself to anti-colonial activists who (then as now) included both left-liberals and anti-Zionists with a national socialist background such as Genoud.

Aldouby and Aigon’s cover story was that they needed to free a Moroccan activist from Spain, and they asked Genoud for help in obtaining a yacht. Their real objective, of course, was to use this yacht to abduct Degrelle. The fact that it had been obtained via anti-colonialist, anti-Zionist and national socialist networks would conveniently have obscured Mossad’s involvement.

Genoud consulted his Moroccan socialist friend Mehdi Ben Barka, who warned him that this smelled like a possible Mossad trick similar to the Eichmann operation. (Ironically Ben Barka himself was kidnapped and presumably murdered in 1965. His corpse was never found.)

Soon after Ben Barka’s warning, Genoud had a stroke of luck that confirmed the real nature of the plot. As I have explained in an earlier online essay, at exactly this time Genoud had been working with the eminent British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper on an English edition of the Hitler-Bormann Testament. Examining this hardback book published by Cassell, Genoud happened to see on the fly-leaf an advertisement for the book on the Eichmann case by Reynolds, Katz and Aldouby.

Though this referred to a “Zwy Aldouby” not a “Herbert Aldouby”, it seemed to be more than a coincidence. So Genoud checked with the head concierge at Aldouby’s hotel in Lausanne, who happened to be a national socialist comrade.

Sure enough, the hotel registration was in the name “Zwy Aldouby”. It was easy for Genoud to work out that an Eichmann-style plan to kidnap Degrelle was under way. Genoud therefore wrote again to Degrelle on 2nd July, informing him of these new developments. It seems likely that it was via Genoud as well as the BND that Spanish security authorities knew enough to be waiting for Aldouby and Feinsohn when they crossed the border.

As soon as the two kidnappers were arrested, Mossad’s cover story came into operation. Mossinson was arrested separately, but there was no clear evidence linking him to the conspiracy, and by one account Israel’s Prime Minister David Ben Gurion intervened with Franco. Mossinson was never brought to trial. He was simply taken to the French border and deported.

On arrival in Paris, Mossinson showed the US Embassy’s legal attaché an Israeli police ID card signed by Israel’s Minister of Police, Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit, stating that the Minister knew Mossinson personally. He flew back to New York, and went on to write many more plays and novels, returning to Israel in 1965, where he died aged 76 in 1994. Mossinson was honoured on an Israeli postage stamp in 2004.

Another member of the team had avoided Spanish security’s surveillance. Carol Klein, a 22-year-old New York Jewess, travelled across the Atlantic from New York to Le Havre with Aldouby and Mossinson on the SS Liberté. She then stayed with them for a while in a Paris hotel while preparations for the kidnap were worked out, before flying to London, while other conspirators headed to Spain.

On 4th July Klein flew to Madrid and checked into the Palace Hotel, expecting to meet Aldouby on his arrival in the capital, and unaware of the fact that he had been arrested at the border the previous day and was now in a Spanish jail. She later presented an elaborate cover story to account for her actions.

Thanks partly to the research in this book, and partly to more recent research stimulated by a BBC documentary about Aldouby’s later mysterious work on a pro-IRA propaganda film which for various reasons also had Mossad connections, we know that the orthodox historical portrayal of Aldouby and Klein as hapless amateurs was concocted by Mossad to cover their tracks.

Carol Klein was a Mossad operative who knew perfectly well what she was doing. She conveniently disappeared from the historical record until I tracked her down a few months ago. In recent decades Klein has become a committed left-wing, feminist activist. Under her married name Carol Mack she has written several plays, as well as teaching fiction writing as an adjunct professor at New York University. Carol Mack, once a key player in Mossad’s plot to kidnap Léon Degrelle, is now best known for devising the “collaborative documentary theatre piece” Seven, in association with a feminist NGO, the Vital Voices Global Partnership.

Mack’s contribution portrayed the Irish political activist Inez McCormack, who became a great heroine for former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, a friend of Mack’s and prominent sponsor of Vital Voices. (McCormack was portrayed in Seven by Meryl Streep.)

Mossad kidnapper Carol Mack’s son Joshua Mack is now Vice-President of New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage, described as ‘A Living Memorial to the Holocaust’. Perhaps one day he will encourage the Museum (and his mother) to tell the truth about the conspiracy to kidnap Léon Degrelle.

José Luis Jerez explains in this book that long after the 1961 plot, and after legal plans to negotiate a ‘judicial kidnapping’ had failed, further schemes were laid by the Simon Wiesenthal Center, whose president Rabbi Abraham Cooper allocated a million dollar budget in 1985 to securing Degrelle’s removal to stand “trial” in Belgium, Germany, or Israel. The Rabbi didn’t disguise the political motives for his pursuit of the near 80-year-old Degrelle who, he said, was “guilty of promoting Nazi ideas among young people around the world. We are going to follow him closely and we will make him pay for this.”

A practical effort to advance the Wiesenthal Center’s agenda came at the end of 1985 when the Venezuelan Jewess Violeta Friedman brought a legal complaint against Degrelle in the Madrid courts, attempting to criminalise revisionist comments he had made on Spanish television and in the Spanish magazine Tiempo whose editor and journalist were also targeted in the same legal action. The court found in favour of Degrelle, ruling that his statements were fully legal and protected under the Spanish constitution’s guarantees of free speech. (Regrettably those constitutional guarantees have been compromised in more recent years by the new law against antisemitism, and the new ‘democratic memory law’, as discussed in H&D articles by Isabel Peralta, but Spain remains more free than the UK in terms of “hate speech” laws.)

A consistent thread running through this book is that Degrelle’s national socialism was not an ossified relic, nor could it reasonably be described as “far right”. National socialism is an organic idea, a living ideology which adapts to be applicable to changing times and to different European cultures. Most of all, it is wholly distinct from reactionary authoritarian conservatism.In 1987 José Luis Jerez gathered commentaries on the twenty-seven points of the Falange Programme. These were written by the most eminent survivors of the Falangist tradition. Authors included Blas Piñar, who tried to maintain a version of Falangism in the late 20th century after Franco’s death with the parties Fuerza Nueva (‘New Force’) and Frente Nacional (‘National Front’); and Ángel Alcázar de Velasco, known to British historians mainly for his work with German intelligence during the Second World War.

Degrelle wrote a commentary on Point 16 of the Programme (‘All Spaniards who are not disabled have a duty to work’). This commentary, reproduced in full in the book, emphasises the difference between national socialism and reactionary conservatism (including Francoism). It also indicates that Degrelle, though by this time aged over 80, had retained a lively intellectual interest in the state of contemporary Europe.

“This duty to work”, Degrelle wrote, “is stumbling upon the material impossibility of working that has hit millions of young people head on. …The real problem is no longer the duty to work, but the duty to be able to work.” He added that the honourable requirement to work was “only conceivable to the extent that a strong state subjects a hyper-capitalist society to the law of the common good, and taming the pursuit of profit, the mediocrity of industrial elites, and the cruelty of competition at any price, which make man a manipulated object according to the very laws of economic materialism. The Falange, inscribing in its principles the obligation to work, inserted in them a sacred duty to do so in a human and balanced society.”

He recalled that his old comrade José Antonio had fought against the leftist ‘Popular Front’, under whose rule workers were miserably paid. On the other hand, Adolf Hitler’s national socialism had not only provided jobs but also decent living conditions, holidays, and an elevated culture.

For Falangists (and by extension for national socialists such as himself), Degrelle argued, class warfare was criticised not only when it was pursued by or nominally on behalf of the proletariat.

“It is also often a fact of the powerful class, committed to enjoying their privileges, the privilege of hogging sterile wealth, and living as such without collaborating for the common good. This class, because of its blindness and selfishness, has also been afraid for social peace, as Karl Marx’s teaching points out. José Antonio wanted to bring this wealthy class to heel, to force it to serve and not just to enjoy; to endow the nation with true elites who considered the manual labourer a respected collaborator and not a servant, whose only value is determined by profitability.”

H&D readers will learn from this biography that the true European cause is at the opposite ideological pole from both the bureaucratic Europe of the Bilderbergers and bankers, and the shallow anti-Europe of Nigel Farage and his fellow reactionary spivs. Nor does our cause have anything in common with state-shrinking ‘free marketeers’ such as Vox, who aim to steer European societies in the direction of American-style capitalism.

In 1992, only a few months before his 86th birthday, Degrelle again demonstrated his political and intellectual agility when he was interviewed by José Luis Jerez for the Moscow-based weekly newspaper Den (‘The Day’). At that time, it was still possible to hope that out of the chaos of Soviet communism’s collapse, some genuine political alternative would arise to challenge Europe’s democratic stagnation and corruption. He therefore emphasised “Russia’s great potential”, if someone could emerge from the chaos “and give decisive support to Europeans who still seek the resurrection of a great ideal.”

I also remember those days of hope, though in my case the hope was quickly tempered by experience of Russia’s own corruption and enfeeblement that was evident in countless ways when I travelled there in 1993. (Degrelle of course at almost 86 was not visiting Russia himself.)

The great warrior who had fought so valiantly against the depredations of the Red Army was not to know that Stalinism would be revived by Vladimir Putin, in a strange hybrid with the worst aspects of Western crony capitalism. In a bitter irony, the very publication in which Degrelle was interviewed, Den, became a mouthpiece for neo-Stalinism after being relaunched as Zavtra in 1993 under the same editor, hardline communist Alexander Prokhanov.

More than thirty years after the interview, it’s unfortunate that its reappearance in this book (divorced from the particular context of those times) might give aid and comfort to Putinist traitors and enemies of Europe, especially when such traitors are so numerous in the ranks of Spanish, American and British ‘nationalists’.

But it’s critically important to remember that José Luis Riesco’s book was first published in 2009 (though only now appearing in English translation). In 2009 it would not have seemed necessary to add context pointing out the very different direction that Russia has since taken under Putin, which only became unmistakeable to outside observers from about 2014, twenty years after Degrelle’s death. It remains true that (as Degrelle clearly believed in his later years) Europeans might need to look eastward to revive our ancestral spirit and escape from liberalism and materialism. But it’s now obvious that such a liberation cannot come from the neo-Stalinist Putin, whose crumbling Russian empire is inherently semi-Asiatic, mongrelised and corrupt to the core. The revived Europe that Degrelle sought will come rather from the blood sacrifice of Ukrainian patriots, and the determined anti-Kremlin resistance of a new alliance of Europeans stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea – the Intermarium once dreamed of by Adolf Hitler and his chief adviser on Russia and Eastern Europe, Alfred Rosenberg.

In most respects this is an admirably produced book. The only small errors I spotted were towards the end where there is some confusion of dates and ages (i.e. in 1993 Degrelle was 87, not 93). Unlike many translated books, the English text is superbly readable and conveys the inspirational character of a man who remained until his dying breath a loyal national socialist, but one who, far from resting on the laurels of his own youth, was determined to inspire today’s youth with the same passion for the true European cause that had driven his comrades and himself to fight in our continent’s epic conflagration.

We should leave its heroic subject with the last word, speaking on 20th April 1989, the centenary of the birth of the Führer for whom Degrelle and his young comrades from across Europe had sacrificed their youth in an anti-Bolshevik crusade:

“My dear comrades, you need to be strong and have faith. We are in a unique position, when everyone has capitulated, immersed in a capitalist civilization, if you can call it that, where people only think of vulgar things, we are the bearers of a doctrine that brings happiness to people. We are the bearers of an immense historical memory, such as Europe has never seen and as the world has never contemplated. All of this was because of Hitler, and it is because of him that we are gathered together tonight thinking about him. In spite of everything he had to suffer and the outrages he had to endure, we cry out with all our strength, Heil Hitler!”

Reviewed by Peter Rushton, Manchester, England